Introduction

"Man is the measure of all things, of what is and that it is. Of what is not and that it is not,” said Protagoras. This famous quote contains the essence of Protagoras’ teachings and aptly reflects the Sophist school of thought, which is accepted in a different form to date. Through these words, Protagoras implies, every individual has a different perception about various things. Hence, every person has his own yardsticks to gauge things. Therefore, the sensations and perceptions of an individual are the ultimate truth and hence, true wisdom and knowledge does not rely upon others.

His words contradict the psychology of other ancient Greek thinkers who distinguished senses and thoughts between individual perception and logic. These thinkers propounded, ultimate truth cannot be merely defined by sensations but also requires reasons to understand any particular thing, occurrence or phenomenon. Though often reviled for his preaching that belied accepted ones in ancient Greece, Protagoras carved a niche for himself because he preached that nobody can foist one’s opinion upon another and claim it is the absolute truth. Hence, he is also famous as the Father of Relativism and the Father of Agnosticism- which promotes the thought that all individuals are free to denounce or accept any belief and the concept of “maybe”.

As with other pre-Socratic thinkers, very little is known about Protagoras. Renowned Greek historian and chronicler, Diogenes Laertius in his book ‘Lives and Thoughts of Eminent Philosophers’ unsuccessfully tried to reconstruct the life of Protagoras, some 600 years after the thinker existed. Plato and Aristotle mention Protagoras in some of their works. However, these are highly unreliable since the two bore antipathy against Protagoras, and hence, could be biased. Further, Plato was too young when Protagoras flourished and hence, it is most likely the two never met, thus his opinion about the pre-Socratic thinker could be flawed, say historians.

According to available information garnered from various sources, Protagoras was born in Abdera in Thrace in 490BC. There are no details about his ancestors leading historians to believe Protagoras was born in an ordinary Thracian family. Details about his education are also lost to antiquity.

Protagoras is believed to have migrated from Thrace to Athens around 470BC. Aristotle claims Protagoras once worked as a labourer and porter, lugging heavy objects- notably, wooden logs- for a fee. Once in Athens, Protagoras associated himself with various thinkers and imbibed their teachings in the Grecian capital, which was renowned as the seat of thought and higher education. Ancient Athenians adulated thinkers and their followers. It is believed Protagoras possibly studied under Democritus, or the ‘Laughing Philosopher’ from his native Abdera, who theorized that human perceptions are based on atoms released by idols or objects around us. In due course of time, Protagoras developed his own theories based on other contemporary prominent thoughts, mainly related to psychology.

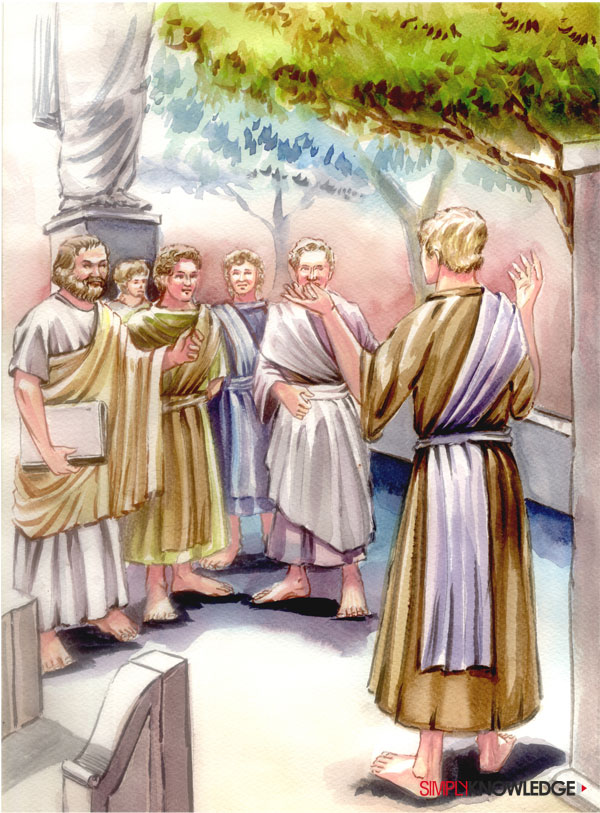

His teachings soon earned a wide following, encouraging Protagoras to charge a fee from students. Some historians claim, Protagoras was the first ancient Greek thinker to charge his students for teaching.

Protagoras was probably the first Greek to earn money in higher education and he was notorious for the extremely high fees he charged. His teaching included orthoepy or the correct pronunciation and appropriate use of words, rhetoric and public speaking, critical appreciation of literary works and Athenian laws on a variety of issues ranging from personal litigation to nationality.

Protagoras is often criticized by historians for charging exorbitantly for teaching while other contemporary thinkers did not charge a farthing. However, Protagoras’ teachings were much in demand since his teaching methods were focused and aimed at empowering students with various skills required to become successful aristocrats. His teaching éclat was lively and included lectures, oratory, critical appreciation of poetry and group discussions on orthoepy and decorum for proper conduct and speech. “Let us hold our discussion together in our own persons, making trial of the truth and of ourselves,” he would tell his students before commencing a debate.

Despite widespread criticism for charging high fees the bourgeois could not afford, Protagoras continued to teach unabashedly. The reason was simple: His pupils came from wealthy aristocratic and trading families. Further, rhetoric and oratory were considered vital skills to political and economic success. Of particular interest were Protagoras’ teachings on Athenian laws, since the local courts were encumbered with litigations of various natures. Locals considered winning a case, however small, as socially significant.

During Protagoras’ time, Athens followed a rather unique legal system. Personal prejudices, political disapprobation and commercial contentions were referred to courts. The affluent and the proletariat Athenians vied with one another for special privileges from the state, through courts. Athenians, regardless of their position in the societal echelons, could not hire lawyers: They had to personally present and argue their cases. Hence, the well-heeled found Protagoras’ skills teaching fiery speeches combined with rhetoric were a great asset to the wealthy trying to scotch attempts by rivals to arrogate their business interests and wealth. “There are two sides to every question,” he said, while teaching students how to turn tables against an opponent in court through cross questioning. The crux of his teachings about law centred over creating self doubt in the minds of the opponent.

Already inflamed over charging iniquitous amounts for teaching skills useful in courts while digressing from established protocols of imparting free knowledge to followers combined with nefarious teachings on how to overcome a weaker adversary soon earned Protagoras the ignominious title as “The Slick Lawyer” and “Mr Wisdom,” among other contemporary peers. Plato, in one of his works, mocks Protagoras for using wily speech and slithery teachings saying earned more than a dozen reputed stone sculptors of ancient Athens.

Unfazed by derision, Protagoras continued teaching his students the seven vital modus to win cases: narration, appeal, entreaty, promise, interrogation, answer, judgment and its implementation. Protagoras’ fame as a teacher of public speech, especially in courts, far exceeded that of Protagoras the psychologist.

His reputation reached its zenith when Athenian aristocrat and general, Pericles, invited Protagoras to debate moral problems faced by the society. Pericles, enamoured by Protagoras’ skills, knowledge and abilities to debate, soon commissioned him to write a code of ethics for the newly acquired Athenian colony, Thurii, around 440BC.

Protagoras, historians claim, authored several books during his active years. Two of these are titled ‘About the Gods’ or ‘Peritheon’ and ‘The Truth’ or, ‘Alethia’. The first book contains Protagoras’ thoughts about Athenian deities. Though purely based on psychology, the book is the first known treatise about agnosticism, as it exists to date.

‘About the Gods’ begins with Protagoras’ famous quote and the byword for agnosticism: “Concerning the Gods, I am not able to know to a certainty whether they exist or whether they do not. Because there are several things which prevent one from affirming so, mainly due to the obscurity of the subject and the short lifespan of humans.”

Commoners, already enraged by Protagoras’ teachings favouring the wealthy combined with his utter disregard for accepted Athenian traditions, were eyeing an opportunity to settle scores with the thinker-teacher. And Protagoras, complacent due to his fame, gave them a gaping loophole through his book ‘About the Gods’.

Athenians termed the opening verses, an epitome of agnosticism, as sacrilege. Unverified records claim Protagoras was charged of impiety by Pythodorus of Anaphlystus, who was considered a Persian vassal after the Athenians fast lost territory to the Persia during the Peloponnesian war. Pythodorus allegedly wanted popular support and the charge of impiety against Protagoras appeared to be the easiest manner to earn it.

Protagoras stood trial for his alleged sacrilege. Paradoxically, the man who taught the Athenian wealthy to win trials in court, lost his own, despite his best efforts to outwit the accusers, who far outnumbered his ardent supporters. Sensing public mood and possibly recognizing the efforts of Pythodorus to save Athens from being ruled by Persian oligarchs, Protagoras said: “No intelligent man believes that anybody ever willingly errs or willingly does base and evil deeds; they are well aware that all who do base and evil things do them unwillingly.”

The court found Protagoras guilty and ordained, all his writings to be burned in public. His detractors jeered at Protagoras and his disciples wept while his works, compiled painstakingly over several decades were consigned to flames.

There are no extant records about how or when Protagoras died. Writings and biographies compiled by later historians indicate Protagoras breathed his last in 420BC, in Athens, due to old age. A few believe, he fell victim to the second wave of the deadly bubonic plague that swept Athens around the time. Other tales claim, Protagoras drowned while sailing to Sicily. None of these claims have been conclusively proven.

While ‘gadfly’ or the adeptness of responding to a question with another is generally credited to Socrates, it was originally invented by Protagoras. The skill, in modern times, is called the ‘Socratic Method’, since Socrates popularized it.

Protagoras is also credited for devising the first known and recorded method of legal arguments in court using seven points: narration, appeal, entreaty, promise, interrogation, answer, judgement and its enforcement. These skills used for presenting a case are based on unnerving an adversary by using psychological skills. The fact that Protagoras found such a wide following within the Athenian affluent is testimony that psychological pressure helped several of his pupils win cases.

Protagoras tried to address and solve a major conundrum faced by contemporary thinkers: “Can individuals imbibe virtue?” Protagoras never claimed he could teach what ancient Athenians defined as ‘virtue’. He propounded that ‘virtue’ by the corollary of ‘knowledge’ gained through experiences, cannot be taught per se. In his doctrine on relativism, Protagoras said, for several subjects or life matters, there can be no definite facts that can be accepted as the ultimate truth. Hence, education in these subjects would be useless. However, through relativism, he explains that individuals do not need to abrogate their own opinion about anything, unless they are convinced that it is not the truth.

By his quote “There are two sides to every question,” which he would often use during his teachings, Protagoras tried to define that individuals often tend to look at anything from their own perspective and not merely the commonly accepted ones.

Though consigned to flames, Protagoras’ work ‘About the Gods’ is the first recorded treatise on agnosticism- which means, an individual is free to believe in or deny the existence of something, especially a spiritual power or god. Agnostics adopt the middle-line of “maybe” meaning, they neither refute nor accept the existence of anything, including the presence of a divine, ethereal power.

Agnosticism, as defined by Protagoras, is practiced to date, though it is widely reviled by various religions and their spiritual leaders for bordering onto atheism. Yet, Protagoras believed that every person is free to form their own opinion and hence, the belief in a god was subject to this personal opinion, which he considered as supreme.

Protagoras laid great emphasis on the correct use of words and their pronunciations, especially for oratory. The reason was simple: Proper knowledge of the vocabulary is essential to convey myriad issues concisely. This method, in turns, results in a greater psychological impact upon the audience as compared to long-winding talk. The manner in which words are pronounced also has a positive or negative impact on listeners- a fact proven by some modern day leaders, who possess the ability to make their audiences cry, smile or ponder.

Next Biography